I like a bit of elitism, but sometimes it can go too far. Jonathan Jones, Renaissance art fan, isn’t the best arbiter of what’s happening at Weston, but, yet, see his review. He starts with a joke about the town’s condition, followed by a whinge on his own ennui at Dismaland – now fully operational at The Tropicana, a dilapidated sea-front lido. Jones doesn’t get the détournement; it reminds him of Rhyl. But the best line of his review has to be when he states that Dismaland ‘was a mere art exhibition. [It] does not offer the energy and danger that real theme parks do.’ So, with all the analytical insight of a thirteen year old theme park enthusiast, Jones writes-off this significant expression of contemporary art and performance. He begrudges rather than celebrates its location, the heterogeneity of the artists involved, the mimesis of theme park labour, and the importance and performance of space. Here are my impressions from my visit yesterday.

D.D and I didn’t know if we were going to get in. We hadn’t bothered to buy tickets and I, keen to experience full dismal-ity, wanted to queue – do the performance of the theme park tourist. We joined the lines just before nine with a bunch of other walk-ups, some who’d slept rough, some having a joint or cappuccino, some elderly, in wheelchairs, and some with enviable camping accoutrements. There were barriers erected as far as the eye could see. There were no staff, merely signs saying things such as ‘all tickets sold out’. And yet hundreds of us waited. That’s D.D, waiting (below).

Two hours passed. The first online ticket customers arrived – and entered. We – the walk-ups – sat in the dirt, getting to know each other, taking the piss of online ticket-holders. Four hours passed. Nothing happened, other than this: we all hypothesised about the waiting. Was it part of the Dismaland experience? We all wondered why online ticket buyers would want to miss out on this important self-parody, this performance of the excesses of tourism that we’d willingly constructed and the more subtle performance of difference between the walk-ups and online buyers. We all burnt. Sun cream was passed around. We acknowledged our own complicities in this hellish act. We reflected on the stupidity of our own consumerism. We started to feel collectivised. And, then, we broke ranks. Two guys on the other side of the barriers offered D.D tickets for him and me at face value. Without hesitation I jumped the fence into the art-patronising-organised-person queue and said sorry to those still waiting. I was delighted to have my bag searched for sharpies. I was ecstatic to be the one with a white ticket, and I was thrilled to be shouted at by punitive security – in one apt performance of theme park labour in Bill Barminksi’s installation. So I’d been rehabilitated as a smug individualist arts consumer, but something about it had embarrassed me. But so what? We were in.

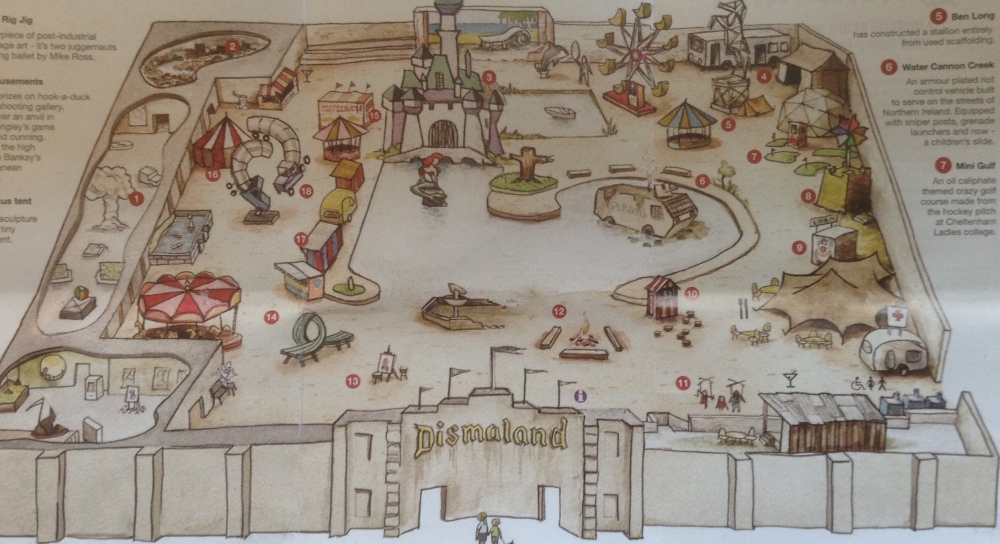

We were in the confines of the 1937 Tropicana site – a large square walled construction, which looks like a fortress; it’s big enough to hold several thousand people, small enough to see everything in one go.

Despite the sea-front location, the ocean view is completely obscured by the original wall – reminiscent of the Berlin Wall in its ability to perform a disturbing presence beyond its physicality. Then there’s the entrance, which you miss as you walk through. The original building, now imprinted by human shadows and the word ‘mediocre’ spelled in spaced rectangular capitals, is eerily reminiscent of the Eastern Bloc.

So between these nightmarish walls is a more British symbology – decaying seaside paraphernalia – Nettie Wakefield drawing the back of your head, a punch and Julie show (sic), a burnt-out caravan turned into a community library, an outdoor cinema showing reels of shorts, a circus tent displaying excellent protest manifestations (heart Ed Hall). There’s a Comrades Advice Bureau and Anarchist bookstore (distributing AK Press – including novels by D.D Johnston) and all of this interwoven with spoilt Americana and references to state violence (see Cameron drinking pinot or whatevs.) and all the omfgs of capitalist excess.

Then there’s the widely reported burnt-out Disney castle, holding the Lady-Di-referencing carriage crash of Cinderella. This literally floored the six year-old in front of me, but she still wanted to buy the picture of herself, shell-shocked and shrieking, encountering the turned-over carriage. Next to the castle are the equally populised merry-go-round, complete with horsemeat scandal installation, picnic area by Michael Beitz, big jig rig by Mike Ross, and perhaps, for me, the most incendiary installation of the exterior site: Banksy’s miniature boats at miniature white cliffs, which kids can operate for a £1, packed with migrants.

The kids navigated around drowned people and tried not to capsize their own vessels, their parents tactically omitting the meaning here, yet forced by their kids’ early understanding of £££ to pay for a go. The performance is in the inter-generational discourse surrounding the whole thing. It’s hilarious and horrific – and costly if you’re a parent. If you’re not, kids’ expressions of the ‘I wants’ are even more shocking.

So the pecuniary aspects are weird. Firstly, we’re imbecilic – all of us. We’re encouraged to spend here, programmatically. Kids drive boats of dying migrants, they’re encouraged to get payday loans and ask for balloons and print outs. And, adults, once you’re in, naturally, you’ll want a souvenir book (£5), have a go on the Ferris wheel (£2), have a go on the oil spillage crazy gulf (sic) (£1) and you’ll probably want a pint (£4) and a pizza (£8) or falafel sandwich (£5) (or all of the above, like us). D.D paid for someone’s drinks on card so we had £20 cash for food (you can pay for drinks on credit – as many as you can afford!). But the money thing, for this ‘entry-level anarchist’ site, certainly referencing commune/squats all over Europe, feels really tricky. I’m all for the hypocrisy that we’re forced to perform here – the necessity to spend money to engage with the vulgarities of our Western status (do play crazy gulf and continue to contribute to the impending ecological crisis!). But, for me, the food was the main glitch in the matrix. For a start, I had pizza with pear – pear – on it, outside London. The sustenance, then, is aimed at a certain type of consumer – veggie, virgin olive oil drizzling, pine nut toasting, recycler. So, for me, it worked, but I felt that it significantly disrupted the artifice of the site which is otherwise mesmeric – both prophetic and catching at strands of past: our childhood (those weird spooky plastic trees we used to play on in desolate pub car-parks) reflecting a Britain overwhelmed by post-war American/Japanese imports, the dissonant glittering sphere of consumption and the bleakness of the material reality. And even (super camera shy) I wanted my photograph taken – which is quite unheard of, but here it is (below).

The workers are significant too. For me, they constituted a performance element that functioned to turn the potential stasis of installation into something live. The workers, in luminescent jackets, and Mickey-Mouse ears, all parade the site – at snail’s pace. They are rude, bored, refuse to sell you the balloons they’re supposed to be selling (balloons which read: ‘I am an imbecile’), and they loll about on the deck chairs and litter the site. They perform a kind of hyperbolic personification of the zero hours worker stereotype – they play with their phones in the internal exhibition, drink, shout insults at you from the side-lines, and refuse to let you use the toilet. All of this is highly enjoyable.

The internal studio space commences with another Banksy piece – an almost full-sized bumper car installation, from which Death – squeezed into a bumper car – spins around convincingly to Staying Alive (I think it was). Dietrich Wegner’s done a baby, in utero, inside a vending machine that pivots on a metal spike and Caroline McCarthy’s piece was an exceptional study of foodsumerism.

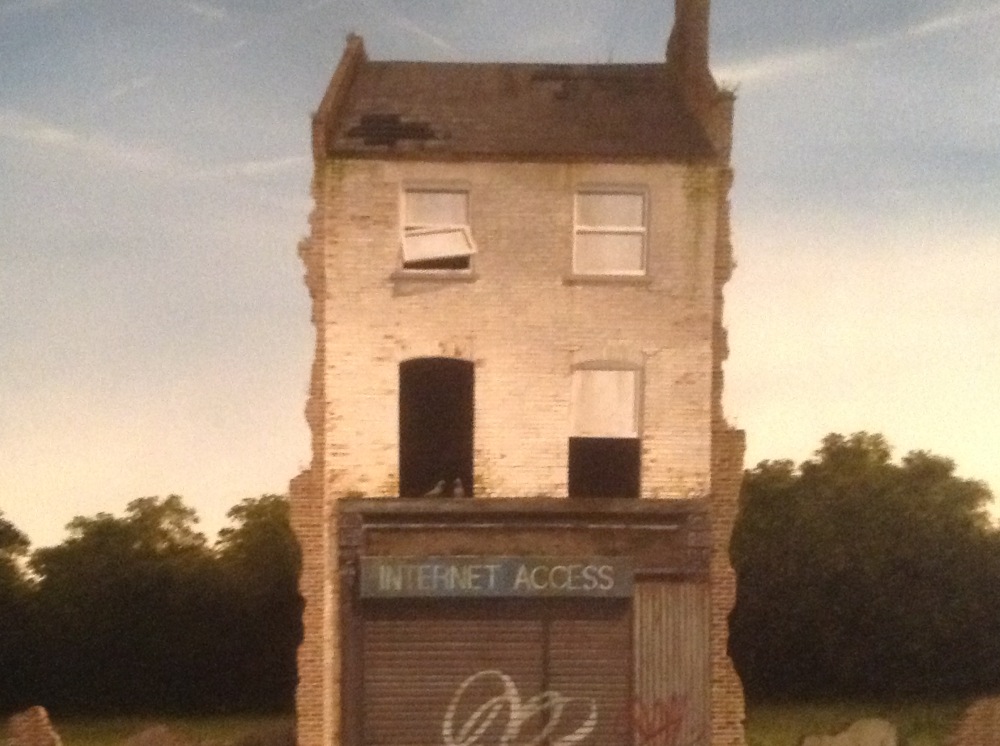

Two more rooms follow, with a stunning Margritte-esque piece from Lee Madgwick (below), notable work from Laura Lancaster and a corker from Damien Hurst.

But here’s the anarchist thought: of course it’s all a bit problematic. The artists are implicated in the mechanisms they clearly want to critique – to a certain extent. Blah blah. This isn’t about revolutionary politics. And maybe art that’s still about explaining/warning about capitalism could be banal, but I, for one, don’t know how. This isn’t supposed to be a consciousness raising expression about state violence and ideological repression, consumerism, (British) apathy; these are the raw materials from which these artists make stuff – that’s all. The phrase ‘entry level’ anarchism is slightly misleading because it suggests there’s a genuine endeavour here to inform people about something that incites change (anarchism), implying that this is also the goal of the art. But, unlike anarchism, which does represent genuine change, art can only send out messages. Dismaland does have a message; as Banksy says about the whole project:

“[It’s] an attempt to build a different kind of family day out – one that sends a more appropriate message to the next generation – sorry kids. Sorry about the lack of meaningful jobs, global injustice and Channel 5. The fairy-tale is over, the world is sleepwalking towards climate catastrophe, maybe all that escapism will have to wait.”

But something else, and something crucial: although art can only send out messages, incite, Dismaland goes further than this, which maybe renders its status a little more politically complex and interesting. Dismaland is in Weston. It gave citizens a thousand free tickets and preview status for the first days of the show. It is the first time such a significant contemporary art event has graced the South West. It was impossible to get a hotel in Weston (for the first time, like, ever) and the trains and car parks and campsites were packed. Of course Dismaland can’t be construed as particularly anarchist because of the positive economic impact it will make on the town, but what is politically important here is the demographic shift that Dismaland – and Banksy – has inspired in art spectatorship. One thing anarchism strives to do is to disrupt conventional hegemonies and power structures. And Dismaland then might be called anarchist simply because of the response it has both engendered from working class people and elitists respectively.

Perhaps the pizza pear thing is a comment on the hipster’s diet. That is, placing incongorous ingredients on otherwise edible food for the sake of being weird different, and not out of taste.

Perhaps not.

LikeLike