Summer, for academics, can be miserable. Campus is alien and empty, and, thanks to all those instagrammed sunsets, researching feels like lunacy and your own out-of-offices come with some kind of biblical wrath. This summer is the first I’ve decided not to go away; I’ve resolutely stuck it out in Gloucestershire trying to write and grow veg (with equal effort). It’s been great, but I do wonder that, come September, I’ll think why the hell didn’t I do anything. I did do one thing though which seemed important in lots of different ways. I’d made a play this year called Voices from the Forest. And a couple of weeks ago, along with my MA student playwrights and Dreamshed Theatre Company, I toured the play to Buxton Fringe Festival with a company of actors—Murray Andrews, Sarah Hancock, and John Martin Stephens—and our director, Bill Cronshaw.

Since this is my first blog post, some context: I’m from Macclesfield, a smallish industrial, mill-framed market town, backing onto the Peaks, fifteen minutes from Buxton. I’ve done plays in lots of different places: Washington, London, New York, Cheltenham (where I’m based), but I’d never worked so close to ‘home’. So something about bringing the play—and the company—to Buxton felt exciting on a personal level.

Voices from the Forest was a commission I received this time last year from the Friends of the Dymock Poets and the Edward Thomas Fellowship. The relationship between me and these groups is that I work at the University of Gloucestershire, which houses an archive and special collection of the work of the Dymock Poets. I’ve written about the creative process of making this play elsewhere, but, just to summarise: it was a dramaturgically gargantuan task which took us deep into the collection, the first editions, related press, criticisms and emotive psychogeography of these poets’ work in Gloucestershire. I realised pretty much immediately that I wanted to share this work with my MA playwrights.

Luckily, where I was dazed by the enormity of filtering all this literary history into the play, they were engaged and forthright and came up with an ace methodology. We decided that we’d include instances of all of the poets and their work in the play, that we’d try, somehow, to represent their life and legacy and we’d deal with a poet each. Ash Hartridge focused on Wilfred Gibson, Chloe Biggs looked at John Drinkwater, I looked at Robert Frost, Matt Pinnell looked at Lascelles Abercrombie, Senja Andrejevic-Bullock looked at Rupert Brooke, and our director, Bill Cronshaw, looked at Edward Thomas.

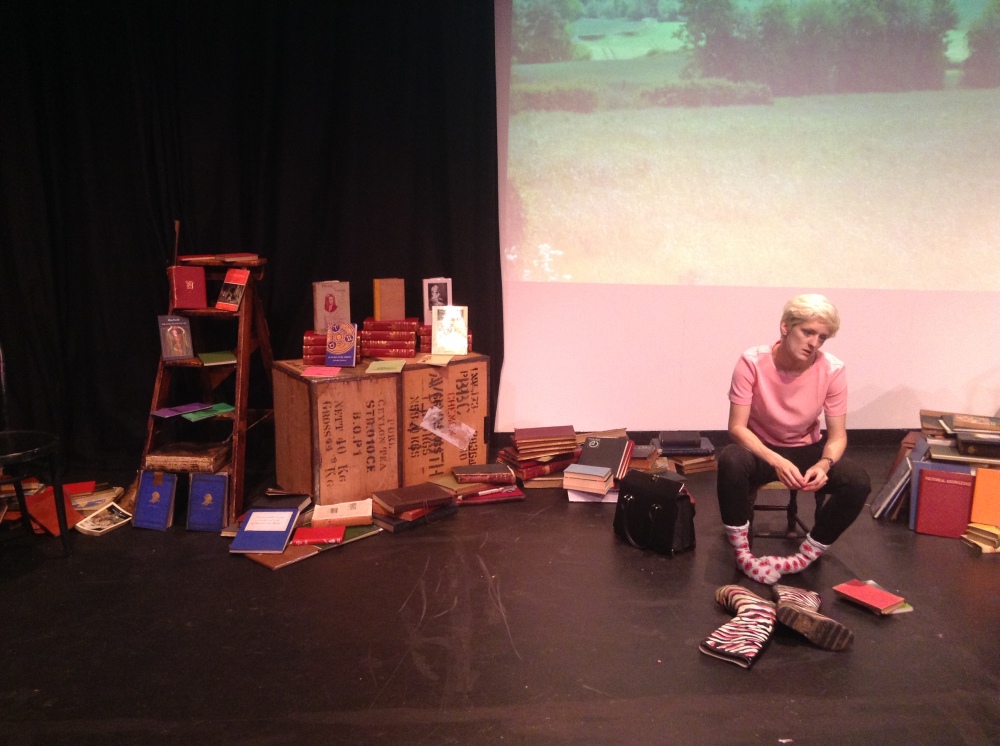

The play focuses on each of the poets in turn, telling their stories from the POV of a group obsessing over the poets. They’re gathered together in a bookshop and have the opportunity to tell their stories. We had a first run of this play in June at the Cheltenham Everyman. And our set looked something like this:

What was really good about doing the play in Cheltenham was the audiences’ existing knowledge of the local landscape. We had a slideshow running of the Gloucestershire landscape and notable locations mentioned in the Dymock Poets’ work. This intrinsic link of the landscape with the audience enhanced the reception of the play. We’d also commissioned an original composition for the play, by Ian Higginson, designed to further reflect the Gloucestershire landscape. When we took the play to Buxton, however, I was worried that the most important element, the pyschogeography of Gloucestershire, and the audience connection to it, would be lost. I needn’t have worried about that; plenty of other things about moving from the comfort of a studio to a fringe venue took precedence. Our set here was literally a ladder, our scant Dymock poet display that the quirky shop-keeper wants to ‘keep tidy’, and our wheelchair for Isaac (Ash’s character, obsessed with Gibson).

Tech was kept to a minimum, which was good, since that was my role. We ended up dispensing with the photos of the Gloucestershire landscape for this production and I don’t think it mattered: we sold out almost every night and I was pleased with the two reviews we received from the official fringe guide and fringe guru. What struck me most about the whole experience was two things: the first is that no-matter how sparse a production and no matter how primitive its realisation, you can’t detract from good writing decisions, nor hide bad ones. The quality of the pieces was still obvious in this setting, as were some of the rawer elements: the fact we hadn’t had enough time once the individual pieces were written to think about how repetitive the form might be or how we might have creatively woven the work together more thoroughly. The second thing that seemed really important, on reflection, is how much playwrights learn from being on the job. The MA playwrights had seen one production of this work already, but to experience it in different conditions—at a fringe—was really useful for them. Also, with a glut of other plays to see, and the notoriously good weather in the North West, we ended up having a bit of a holiday too.